Setting up his Village Trust in 1904, Joseph Rowntree hopes that New Earswick will be a model for more village communities. But building work starts six years before Henry Ford’s first Model T rolls off the production line and 26 years before everyone over 21 can vote in a general election. How does his vision stand up and what challenges do our communities face today?

How do we sustain our communities? Who are our neighbours? And how do we plan new communities?

How do we sustain our community?

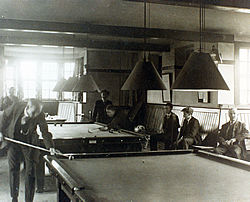

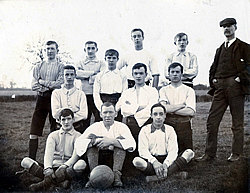

Joseph Rowntree sets up his Village Trust to build and manage New Earswick in 1904. The first general election in which everyone can vote on equal terms is still twenty-four years away. But Joseph wants residents to take a large part in the decision-making for their community. The Village Council established in 1907 is the first attempt at this. Today a 15-strong, elected Residents Forum represents residents’ interests. And elsewhere in York, the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust – like other housing associations – has been testing out various forms of tenant participation, to give residents more say in how their community is run.

By the 1990s, national policy-makers are looking at ways of bringing residents to the centre of regeneration. Changing decision-making from ‘top down’ to ‘bottom up’ becomes a priority in neighbourhoods which have faced years of disadvantage. In 2002, the JRF sets up a Neighbourhoods programme to help 20 communities pool their experience of ‘what works’ in regeneration.

But our community spreads further than the neighbouring streets. As the relationship between local and central government changes, local councillors face new challenges. And, away from elected government, a 1997 survey finds just under half the population involved in voluntary activity. But the numbers of young volunteers are falling. Young people define ‘charity’ and ‘politics’ in new ways; so our community may need to find new ways of engaging them.

Who are our neighbours?

One hundred years ago, other Victorian businessmen have also built model villages, such as Port Sunlight in Liverpool and Saltaire in Bradford. But New Earswick is different. Joseph Rowntree never intends it only to house his factory workers. And, from his work on the slums of York, he knows how poverty can become concentrated into particular areas. He does not want New Earswick to “bear the stamp of charity”.

Throughout the century, slum clearance in Britain continues. More social housing is built, especially after much housing is damaged in the Second World War. New styles of building – like tower blocks – are introduced: in the mid-1960s, JRF research from Pearl Jephcott warns of impending problems. And in the 1970s some council housing is showing signs of poor repair. In the 1980s, much of the most desirable council housing is sold through the Right to Buy.

In 1993, Building for Communities by David Page warns that housing associations – by letting only on the basis of acute need – may unwittingly be creating areas of last resort for the socially excluded. Over the next decade, ways of balancing communities are trialled, such as community lettings. Flexible tenure and shared ownership offer those on lower incomes a chance to buy. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, every alternate home in New Earswick that becomes empty is offered for sale rather than rent. The money allows every sold home to be replaced with a rented one elsewhere. This ‘SAVE’ scheme is one way of promoting mixed communities; it matches Joseph Rowntree’s own wish to see his village community house people from varied walks of life. A study of the Bournville Village Trust, in its own centenary year, shows the enduring value of mixed tenure and good quality management.

And – as ever – new neighbours arrive from outside the country. In 1902, some politicians denounce increasing numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe as a threat, even as an ‘alien invasion’. One hundred years on, the issue of migration is still making headlines. The Foundation responds with a new Single Programme Committee – what challenges do our new neighbours face and how can we include them fully in community life?

How do we plan new communities?

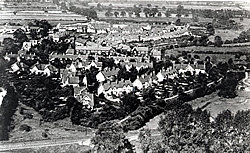

The first streets in New Earswick are very different from York’s Victorian terraces. Influenced by the Garden City movement, they include gardens, culs-de-sac, open space and trees. Cars are not a priority; in 1904 there are 23,000 cars on the road in Britain. But over the years, car numbers increase and New Earswick’s streets need redesigning in response. After the Second World War, new types of housing are built, not just family homes but flats for single people and ‘sheltered housing’ for older people as the needs of these groups are recognised.

By the start of the twenty-first century the need for new sustainable communities has become a national priority to meet acute shortages of accommodation in London and the South, and in ‘hot spots’ – like York – elsewhere. As parts of Britain feel ever more crowded, arguments continue about where we should build. While some homes in the North stand empty, there is a shortage in the South. And everywhere there are problems of affordability.

How we plan is also changing. In 2003, the JRF puts in the planning application for a new 540-home community to the East of York. Local residents have been consulted and a masterplan prepared. Like New Earswick, one hundred years before, the proposed new community has plenty of open space and greenery. The car is now a necessity of modern life; the 2001 Census finds 30 per cent of homes have two cars. But in the new plan its dominance of the street is challenged by Home Zones.

Find out more about the Foundation’s housing

operations,

current research priorities and how it is working to effect

change.